Why do unfair pay practices continue when so many are aware of them? There’s a complex web of unconscious biases and structures at the root of pay inequity. In another extract from our latest white paper, ‘Cultivating Fair Pay in the Workplace: Your Guide to Global Pay Equity’, we take a look at the literature that explains four of the biggest factors acting to perpetuate gender-based pay inequity.

For many groups, the story of unfair pay begins during the hiring process. In countries like the United States, candidates can positively shape their starting pay via negotiation. Studies have shown that women negotiate less. In the past, it was thought that this was primarily because women were less willing to negotiate when given the chance. However, contemporary research suggests that women are less likely to be given that chance in the first place, and are even penalized for attempting to negotiate.

Learn more about Pay Equity in this digital training video.

Furthermore, starting pay is also affected by previous pay—considering that this tends to be less for women, there is a cumulative negative effect on pay in the long term. A recent ruling by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals captured this specific issue. The defendant (the Fresno County Office of Education) attempted to argue that prior pay was a “factor other than sex” when determining starting pay. The court found in favor of the plaintiff, and ruled that past earnings cannot justify pay disparities between women and men.

1) How ‘Aggression’ Myths Undermine Women and People of Color

Starting pay is also affected by a whole cocktail of psychological biases that typically (though not solely) undermine the perception of the worth of women and people of color to an organization. In the long term, these biases likewise affect performance metrics, promotion chances, promotion pay increases, pay raises, and bonus distributions.

A 2018 Harvard research study found that women who asked for a raise obtained it 15% of the time. By contrast, men were found to have a 20% success rate. Similarly, a McKinsey & Company study found that women who negotiate for pay and promotions are disproportionately penalized for doing so. This group of women was 30% more likely than men who also negotiated for pay to receive feedback indicating they are “intimidating”, “aggressive”, or “bossy”. They were 67% more likely to receive such feedback when compared with women who don’t negotiate.

Findings in a study in the Journal of Applied Psychology echo these statistics when considering African Americans negotiating for salary increases. The study found that this group is (falsely) perceived as negotiating more frequently than whites. They were more harshly penalized for negotiating too: for every offer or counteroffer an African American employee made, they received $300 less in salary when compared to their white colleagues.

Consider also, that these differences are played out multiple times over the course of these employees’ professional lives. Over a whole career, small gaps accumulate and widen into chasms.

Also on our blog: ‘Social Injustice and How Companies Can Support Their Black Employees’

2) Why Don’t Women Get to Be Leaders?

In many countries, women are less likely to be viewed as leaders or as having leadership qualities. Again, there are multiple biases at work here, which stem from things such as:

- The association between leadership and stereotypically masculine qualities

- The lack of prominent models for what female leadership looks like

- Traditions that cast women in non-leadership roles.

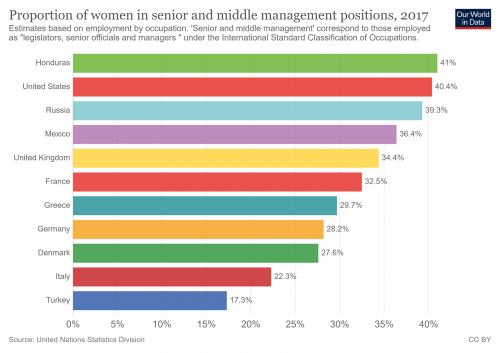

These biases decrease the likelihood that women will become prominent in their field, promoted in their organization, or chosen for higher-level positions within an organization. Given that women make up a bit more than 50% of most populations, the disparity with which women are actually represented in leadership roles can be quite striking.

In the chart above, using data from the United Nations Statistics Division, we can see the percentage of women in senior and middle management positions for selected countries. The lack of women in these positions in the countries of Europe is particularly striking—as low as 22% in Italy.

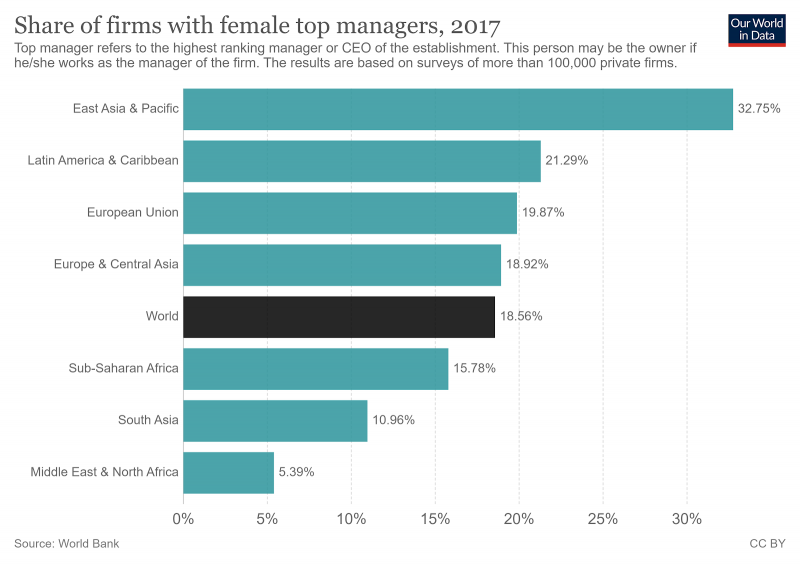

The issue is even more pronounced at the very top, as shown by this second graph revealing the percentage of female CEOs or top-level managers by major region. Worldwide, only around 18.5% of top-flight executives are women—and in the available data, only in the East Asia & Pacific region does this percentage rise significantly above the worldwide trend.

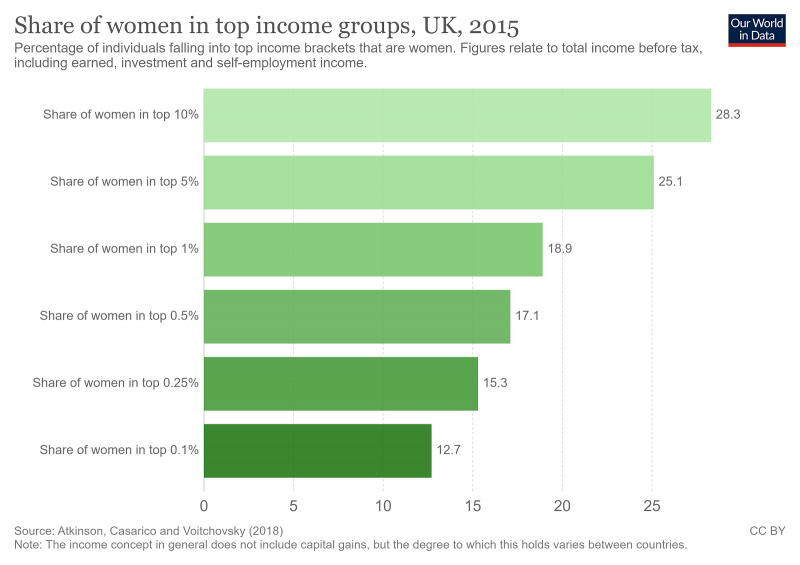

In the United Kingdom, we have already seen that around one-third of senior and middle management positions are filled by women. As a counterpoint, the chart above shows the percentage of women within the UK’s top income groups: as we get closer to the highest 0.1% of earners, the proportion of women in those groups decreases steadily. This suggests that even where women have access to higher positions, they don’t have access to the same levels of compensation.

More insights from the blog: ‘Avoiding Unconscious Bias: 6 Insights That Will Help You Take Action Immediately’

3) The Gendered Profession Pipeline

In many countries, women are also steered away from many higher-paying fields. Sometimes male-dominated fields can become actively hostile to women through a mix of cultural norms and in-group practices: unsociable hours and excessive overtime requirements may be incompatible with childcare responsibilities, for example. Or industries may have a ‘boy’s club’ mentality rife with outright sexism, or a tendency to close ranks whenever negative behavior is called out.

Often, the process is less overt and shaped over many years by society at large. Young girls and women get certain messages from advertisements, pictures, cultural depictions, and role models. The signals imply that they are better suited to certain professions, while their presence in others would be at best a notable exception.

Typically the fields that women are steered away from are those that are higher-paid, and the fields that come to be dominated by women tend to become undervalued over time. Once gender becomes a predominant factor for a field, the education level, effort, conditions, and level of responsibility required by available positions tend to correlate poorly with the degree to which that work is valued and compensated by society.

In fact, several examinations of this effect have demonstrated that pay levels associated with formerly male-dominated roles start to drop when women begin to dominate them.

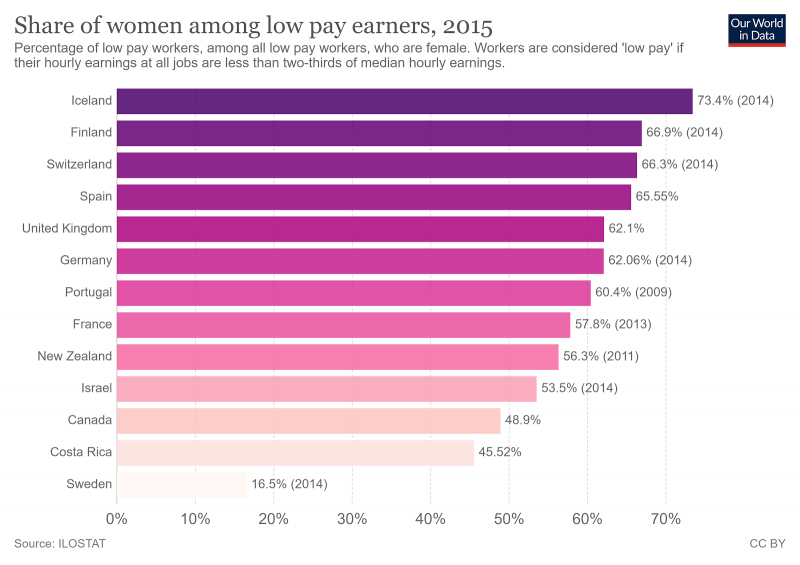

We can again look at ILOSTAT’s data for a variety of countries showing the percentage of low pay earners who are women, and see that even in countries with an egalitarian ethos and strong fair pay laws, women make up the majority of this group.

Making an argument for fairer pay? Discover our Infographic: ‘6 Reasons Why Organizations Should Care About Fair Pay’

4) Family Business? None of Our Business

Women sometimes have children. This is perhaps central to the web of reasons that women are lower paid. Why the further continuation of the human race is quite so under-appreciated by the majority of societies is beyond the scope of this document. Suffice it to say, the immediate reason the ability to have children negatively affects pay is that many companies and the people in them have been, and to some degree still are, resistant to taking on part of the burden associated with child-rearing.

For a large part of their working lives, women will be considered a more risky hiring proposition because they are perceived as being more likely to:

- Require maternity leave

- Request flexible hours

- Go through periods of lowered availability

- Cause the business to incur additional insurance coverage costs

- Leave for family reasons

Additionally, women do not seem to get credit for the non-professional experience they gain when they do decide to stay out of the workplace in order to raise their children. This time is often viewed as entirely devoid of work experience worthy of compensation. Considering that the process of returning to work is itself a challenge that requires skill to navigate (especially in the United States), this perspective can add insult to financial injury.

Reasons for pay differences between other groups of people are similarly complicated, and overcoming these causes of pay inequality is daunting. Yet, for most people and for most societies, the principles they follow make both the pay inequalities and the reasons for such pay inequalities unacceptable. This is why fair pay matters in the larger sense, but it also matters for a number of very practical reasons.

Unfair Pay: Continue Reading

Elsewhere in the white paper we also cover:

- The many different terms and the analytical lenses we can bring to discussions of fair pay. This includes a look at differences between ‘equity’ and ‘equality’.

- The increasingly compelling case for why your organization needs to care about, and take action on, pay inequity.

- A five-step plan of action for organizations that want to create fairer pay practices.

Download your copy of the white paper today.

Inspired to start counteracting the mechanisms of unfair pay built into our world? Contact our team for more information.

About the Author

About the Author

Patrick McNiel, PhD, is a principal business consultant for Affirmity. Dr. McNiel advises clients on issues related to workforce measurement and statistical analysis, diversity and inclusion, OFCCP and EEOC compliance, and pay equity. Dr. McNiel has over ten years of experience as a generalist in the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology and has focused on employee selection and assessment for most of his career. He received his PhD in I-O Psychology from the Georgia Institute of Technology.