When does your organization need to develop an affirmative action plan? While the answer to this question may be relatively straightforward, the deeper nuances of how many plans you should be creating, and how to properly account for your employees in those plans, are a little more complex. In this article, we take a closer look at some important questions you may have about your affirmative action obligations.

When Is an Organization Required to Develop an Affirmative Action Plan?

Though the parameters for AAP eligibility are likely to be something you’ve heard many times before, a review of the specific wording of the scope and application of Affirmative Action in Title 41 is nonetheless the best place to start.

§ 60-2.1 starts with the detail that its requirements “apply to non construction (supply and service) contractors.” (Construction contractors are dealt with separately in § 60-4.1). It then states that a contractor “must develop and maintain a written affirmative action program for each of its establishments if it has 50 or more employees and:”

- (i) Has a contract of $50,000 or more; or

- (ii) Has Government bills of lading which, in any 12-month period, total or can reasonably be expected to total $50,000 or more; or

- (iii) Serves as a depository of Government funds in any amount; or

- (iv) Is a financial institution which is an issuing and paying agent for U.S. savings bonds and savings notes in any amount

While the 50-employee and $50,000 contract threshold is familiar, it’s worth noting the other, lesser-known criteria. Firstly, if instead of providing a direct service or product to the government your organization transports goods for the federal government, you may fall under item (ii). Specifically, if your organization has Government bills of lading for goods that you ship on their behalf, and these are worth $50,000 or more in a 12-month period, you will need to produce AAPs.

Banks that participate in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), or that are serving as a depository of any government agency, also fall under the OFCCP’s jurisdiction. And as per item (iv), the same is true for any financial institution that is an issuing or paying agent for U.S. savings bonds.

FURTHER INSIGHTS ON AFFIRMATIVE ACTION | ‘Lessons From 40 Years of Preparing Leadership for Affirmative Action: Q&A With Veteran Practitioner Ed Johnson’

When Does the Requirement to Develop an AAP Come Into Effect?

Once you understand when an organization is required to develop an affirmative action plan, you’ll need to know when that plan should be put in place. Title 41 states that contractors have 120 days after the commencement of a contract to develop their plans, with a requirement to update and recertify every year. Therefore, as soon as a contract is in place, organizations will want to proactively start pulling together all required information immediately, as the process of creating an AAP can be time consuming.

What Areas of Your Organization Should Be Included In Your AAP?

Though the wording around AAP eligibility is relatively straightforward, there are inevitably questions about the extent to which the requirement applies to the broader organization.

A basic interpretation would be that if any part of your organization is involved in a federal contract or acting as a subcontractor to a federal contractor, your entire company is subject to everything in Executive Order 11246, paragraph 60-2.1. However, companies may argue that certain parts of their organization are not included, and indeed—in a small number of cases—there may be some legal ways to get around a blanket application of the requirement. If you believe that this is the case, please consult your attorney.

INFORMATION ON AAP OUTREACH | ‘5 Key Affirmative Action Outreach Resources (And What You Should Record About Your Efforts)’

Which Employees Should Be Placed in Which Establishment AAP?

As you are doubtlessly aware, affirmative action plans are typically put together location by location (or establishment by establishment). While this approach still largely makes sense, working habits have changed sufficiently in the last 20-30 years that it’s likely many organizations will have individuals who are more difficult to place.

The days when everybody who works in a location reports to someone in that same location are over. Our increasingly virtual workplaces mean that it’s common for team members to regularly work from home, or managers to oversee teams in another office. It’s important for your affirmative action plans to account for this, because the plans ultimately inform your selection activity. If an establishment has people in its plan that it has no control over, that establishment’s ability to attain the goals you define will be undermined.

For example, due to a remote hire or a relocation, an employee may be based in an office in Dallas, with a direct supervisor in an office in Boston. As this employee reports to Boston, and the selection decision was made in Boston, they should be included in the AAP for Boston—rather than in the plan for Dallas.

Typically, these kinds of adjustments are reserved for upper-level professionals and managers. It would be less usual for selection decisions for admin staff or janitorial services to be made at another location, for example.

Ensuring that there is a firm rationale for relocations between plans is important, because though a potential OFCCP audit will nominally be for a single, specific location, these links will prompt investigations of further locations. If an OFCCP officer looks at your audited location and sees a large number of annotations describing individuals who report elsewhere, they will want to do their due diligence and look at plans for those locations as well. Therefore, it makes sense to ensure that these annotations are strictly necessary and properly representative. So again, we recommend that you only list these adjustments for upper-level professionals and managers.

When Should You Create Plans for Under-Sized Locations?

When you have employees who work in locations with fewer than 50 workers, you’ve got a number of options.

For example, you may have a location in Kansas City that has 20 employees. Over the course of the next 12 months, you expect that location to grow to 30 or 35 employees. While it isn’t going to hit the 50-employee threshold, you may decide to create a separate plan for them anyway as it won’t impact your other plans or involve any extra risk. This option also prepares you for growth further in the future, and ensures you will have less additional work to do at the point when the plan becomes mandatory.

Alternatively, you may decide that you want to minimize the number of plans that you’re managing, and § 60-2.1 Scope and Application gives you the option of putting those employees into another plan. If their manager or their HR support is located in another plan, that would be a logical place to keep them too.

A further option would be to create functional affirmative action plans instead of establishment-based plans, an approach where the contractor “organizes its AAP to reflect how the entity operates functionally rather than where its facilities and people are physically located”. This requires permission from the OFCCP. Whatever your preferred method of accounting for under-sized locations or your plan structure more generally, these decisions should be checked with your legal team. That way, you can ensure you’re making the right decision, providing the right information, and not revealing more than is appropriate about your organization.

LEARN ABOUT KEY DATA CONSIDERATIONS | ‘Incomplete, Inaccurate, Inconsistent: How the 3 “I”s Sow Chaos in Your Affirmative Action Data’

How Should You Annotate Your Plans to Account for Included and Excluded Personnel?

Clearly, there are a range of valid reasons why you may need to allocate individuals who work in one location to another location’s affirmative action plan. But how should such decisions be indicated in your plan? Usefully, there are set ways that you can provide this information in your affirmative action plans.

There are two places that you can readily find information about where people are reporting into and out of: one is your workforce analysis, and the other is your job group analysis.

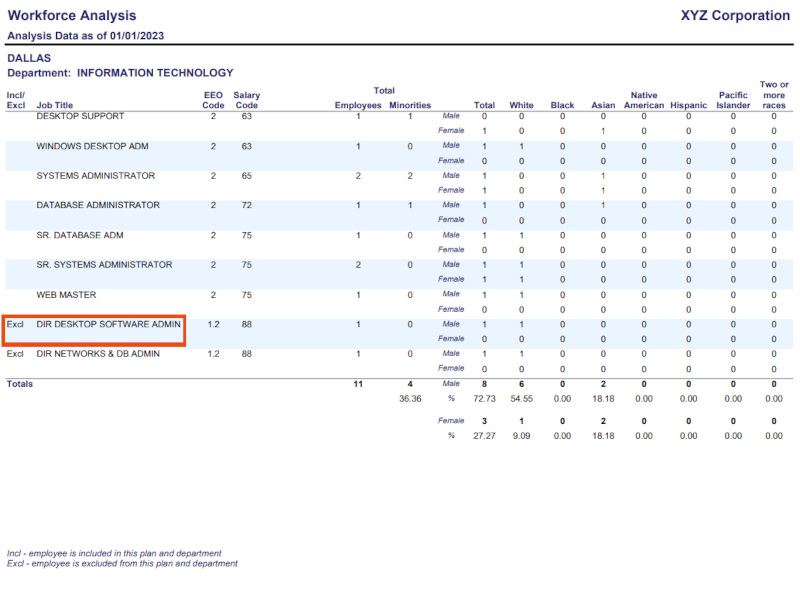

Workforce Analysis Annotation Example

Fig.1: An example of a workforce analysis showing a column for individuals excluded from the plan.

Your workforce analysis provides a per-department view of all of your unique job titles categorized from lowest paid to highest paid (typically top to bottom respectively). Individuals excluded from the plan can be annotated as appropriate—our example above records “Excl” in a specific Incl/Excl column of a Dallas-based plan.

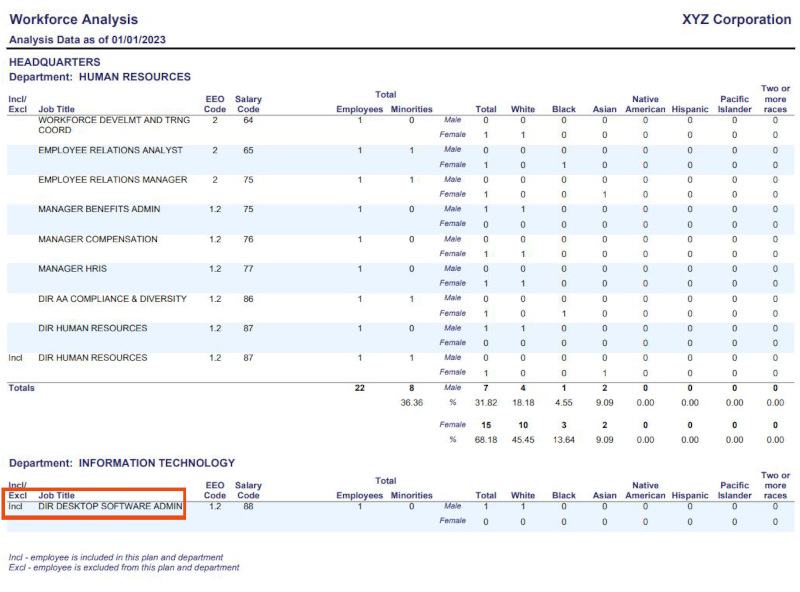

Fig.2: An example of a workforce analysis describing the inclusion of individuals excluded from the plan in Fig.1

In order to properly account for any individuals excluded from a given report, there must be a corresponding record in the appropriate location’s plan. In our example, our Dallas-located Desktop Software Admin is marked as “included” in the workforce analysis report for headquarters, reflecting where they are reporting to.

Job Group Analysis Annotation Example

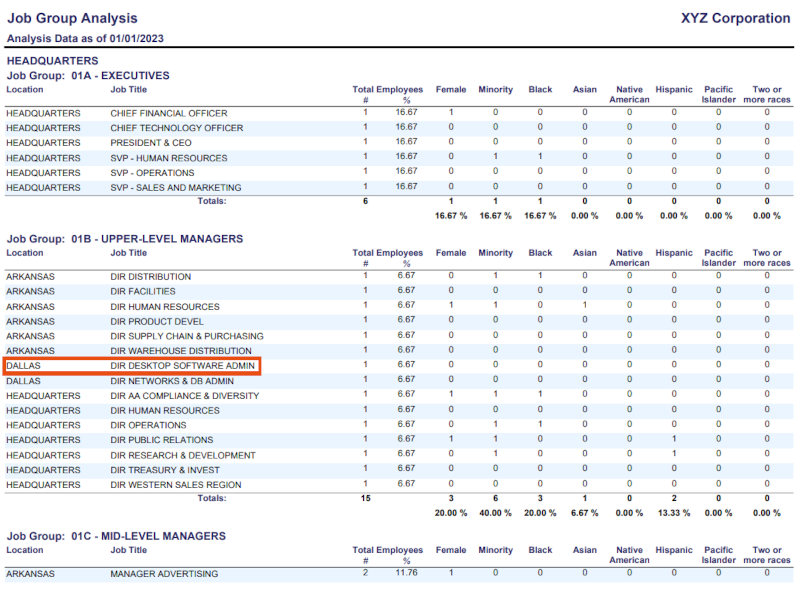

Fig.3: An example of a job group analysis listing individuals reporting into headquarters from different locations.

Providing this information about included and excluded personnel via your job group analysis is a little different. In the example above we’ve shown a job group analysis for an organization’s headquarters, and our Desktop Software Admin is shown reporting into this plan and being counted for utilization purposes. Including them is a simple matter of listing their location as “Dallas” even though this is the plan for headquarters. This individual would simply be omitted from the Dallas office’s plan.

In Conclusion: Understanding When and What to Include

AAPs require a reasonably high degree of legwork and precision in their execution. Though the guidelines on when an organization is required to create an AAP are clear, things become a little more complicated when scaled up to larger, multi-premises businesses.

With the information above you’ll have a better understanding of when you must create an AAP—including conditions outside of the usual 50 employee/$50,000 contract threshold. You’ll also understand that, barring advice from your attorney, you should anticipate the requirement applying to all parts of your organization. And finally, you’ll now also understand how to handle employees who are located in one establishment, but who report into other establishments.

Of course, if you’re making a large number of plans, and manually coordinating inclusions/exclusions across them all, the task may start to feel quite daunting. A robust, software-based approach, such as Affirmity’s CAAMS® software is essential for these larger workloads, helping you assemble the required reports and maintain compliance with ease. Better still, our “TotalView” methodology will give you organization-wide visibility of representation, benchmarking, selection activity, hires, promotions, terminations, transfers, and applicant flow activity. All this information makes it easier to identify issues while being relevant to your wider DE&I goals.

Discover how Affirmity’s software and service solutions can give you a total view of your Affirmative Action data. Contact our team today.

About the Author

Roy Zambonino is a senior solutions consultant at Affirmity. He is responsible for demonstrating and discussing Affirmity’s wide range of DE&I and affirmative action planning products and services with existing and prospective clients.

Roy Zambonino is a senior solutions consultant at Affirmity. He is responsible for demonstrating and discussing Affirmity’s wide range of DE&I and affirmative action planning products and services with existing and prospective clients.

As a former project manager, Mr. Zambonino is able to draw upon the best practices he’s observed over the last 20+ years helping prepare and implement programs. This work has involved companies ranging in size from a few hundred to several hundreds of thousands of employees, and spans across many industries including retail, construction, healthcare, banking, and finance. Mr. Zambonino has a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Business Administration.